Religions are easily the most recognizable institutions in human history. If you filter the thousands of existing religions to those organizations with greater than a million people, then there are over 20 (three with greater than a billion!). Something like 85% of all humans identify with a religion. The practice of religion is so ubiquitous, in fact, that it’s taken most of our history to disentangle our governing bodies from them (still a work in progress in many areas of the world).

Personally, I was raised Catholic in the southern US. Being required to attend church, go to catechism, then attend a Catholic high school never sat well with me, but it took me many years to understand why I felt that way, which I’ve outlined below. Today, perhaps obviously if you’re a frequent reader, I’m about as religious as a tennis ball!

For a long time though, I struggled with the ideas driving my family’s religion – I found myself blaming religion for everything bad in the world – war, poverty, corruption, extremism, narrow-mindedness, etc. I saw it as a cancerous opiate for weak-minded people.

This, of course, was very foolish of me. Since then I’ve learned a few things and recognized what religion really is – a technology!

I’ll tell you a story about what I mean.

Poisonous Berries

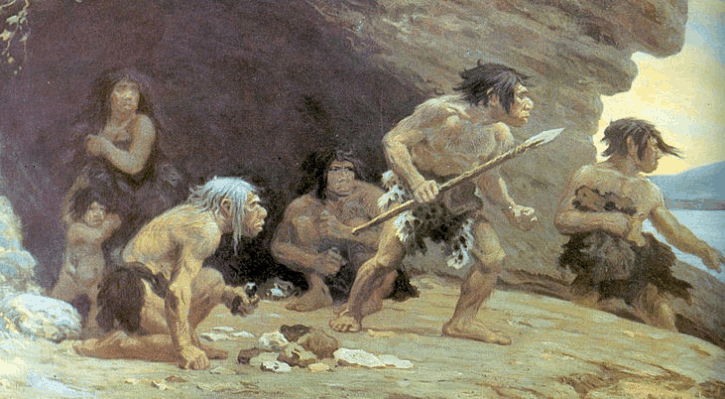

In prehistory, back before the internet, before electricity, before even the widespread development of agriculture, there were ancient proto-humans. These humans didn’t care about what you or I care about today – life was all about food, water, sex, and survival. There was little time for anything else. Life was so difficult and so dangerous, in fact, that living to age 40 meant you were very old.

Because these ancient peoples were so necessarily focused on survival, there wasn’t much time for self-reflection or rational analysis. All they had were each other, huddled together in a brutal and constant struggle for survival. To them, that was the status quo. They knew of no other existence.

There were many things these ancient humans did not understand:

- What are those white dots up there in the dark?

- Where does that ball of light go every so often?

- Why does water fall down sometimes?

- Why does the ground shake?

- What is that colorful bendy thing up there?

Imagine what it took to know the actual answers to these questions; the math, science, discovery, blood, sweat, and tears of countless people building on each other’s work over vast expanses of time. It’s easy to know something someone else told you, it’s much, much harder to discover it for yourself. We take our knowledge of the world for granted. However, these ancient people didn’t have that knowledge. To them, it was all a vast mystery.

Think about survival: When you know something in advance, you can plan to react to it before it kills you. When you don’t know, you can’t. That’s scary; the unknown is scary, and justly so.

When confronted by their uncertain world, these ancient peoples needed a reliable way to understand it in a manner that wouldn’t kill them. Instinctual emotions like fear, suspicion, and caution evolved in all animals due to this need; they are the behaviors that keep us safe.

Imagine you were a hunter-gatherer in ancient times and you’re out foraging for berries. Today, it’s easy to take for granted that the blackberries, raspberries, and blueberries we eat in abundance are delicious and healthy, but there were (and still are) berries out there that can easily kill a person. Choosing the right ones is literally walking the line between life and death. As a hunter gatherer, you need the know-how to make the right choice.

(Yummy!)

(Death!)

But the first hunter gatherer didn’t know.

He saw black and red berries and ate the red berries. Unfortunately, it was the wrong choice. He died that night in agony despite his tribe’s efforts to save him.

However, it didn’t go uncommunicated that the red berries were deadly. The tribe knew from this loss that it was imperative their children be taught to avoid them. They had some options – they could:

- Simply tell their children that the red berries are dangerous

- Make up scary stories about these red berries, associating them with frightening animal spirits that will tear the children apart if they eat them!

Which option might be the more effective lesson to evoke a proper fear of poisonous berries in a child?

Fear is a very important response to legitimate dangers. By passing emotionally-provocative stories down to future generations in various oral traditions, ancient peoples created an inventory of good things and bad things in their world: Good things were healthy and helpful and should be embraced (a good harvest, clean water, good weather). Bad things were painful and destructive and should be feared (red berries, storms, predators). Healthy things were the focus of good stories, while destructive things were the focus of bad stories.

Ever wonder where the concepts of good and evil came from? This is it! Good and evil are merely abstract ideas we created to help us survive. All of modern morality, ethics, and justice grew from the seeds of these survival instincts. We made them up.

Stories passed down by these tribes provided an enduring framework for our ability to navigate our surroundings more safely. However, these stories didn’t remain unchanged. Every new generation added their own influence to the tribes framework and the stories evolved.

Eventually, the red berries and their dangerous “spirits” became one of hundreds of interconnected stories on the tribe’s tapestry of good and evil, descriptively mapping the many aspects of their world. On this tapestry, this survival map, common links and centers between various stories were simplified into greater spirits around the campfire (the red berries could have been “weapons” used in the “war” between evil and good spirits, for example).

Eventually, singular entities were “discovered” at the centers of these networks of good and evil and were held largely responsible for why things are the way they are. Gods and devils were imagined as the central causes of all things and new environmental discoveries made by the tribe were attributed to these dieties in some rationalized fashion. The more “good” (healthy) or “evil” (destructive) the new thing was, the more strongly that thing became associated with these imaginary central entities in the tribe’s storytelling.

This method of thinking gave the tribe a powerful survival advantage: It allowed them to quickly categorize whether a new thing was good or bad, and then retain that understanding for a very long time via storytelling. Think about it: It’s much easier to remember stories than plain facts, especially if said stories evoke an emotion like fear or transcend mundane reality with their fantastical nature. I.e the fascinating artistic mythology and stories of Greek gods and monsters. This knowledge could thus be passed on quite easily to the next generation without that generation having to learn the hard way, i.e. eating the red berries.

This understanding of the world became the tribe’s identity; essentially as important to their collective survival as arms or legs are to you and I. Over very long periods of time, this understanding naturally evolved into the many colorful religions we know today, many of which are the merging of previous religions.

So, in reality, religion was simply our very first organized mental framework for understanding and safely navigating our natural world – a mental survival map; a technology!

The Changing Times

This insight allowed me to recognize religion for what it really is. It made it easier for me to empathize with others about their religious beliefs: Religion is survival in the most visceral way. To criticize someone’s religion is to criticize the warm and familiar identity that has kept them and their ancestors safe from environmental dangers for thousands of years. It’s understandable why this would make a person defensive.

However, the importance of religion to our past does not mean it isn’t wrong. As a way of thinking in modern times, religion is wrong and it is toxic: To hold onto something so tightly that no longer has the value it once did is detrimental to us – it’s no different than stubbornly using an ax when you’ve got a chainsaw handy; a hammer when you’ve got a nail gun; a screwdriver when you’ve got a drill, etc.

We no longer require religion to survive. We now have better ways of thinking about our surroundings in the sciences and modern philosophies. If we are to advance further as a species, we have to let go of our past identities to make room for our new ones. That’s not an easy thing to do by any means, but the solution to that problem lies in educating future generations on the reality of religion’s role in humanity’s evolution. Once one possesses that historical context, it’s much easier to appreciate religion for the wonderful survival tool it’s been for our species, recognize it’s flaws, and grow beyond it.

Yet, change is hard. It will be quite a while before we collectively gain enough maturity to transcend religion. But why is it so hard?

Overcoming Spiritual Addiction and “Faith”

The field of psychology naturally provides many insights on what drives people to do what they do. Religion is no exception. Indeed, it’s extremely important to recognize the psychological factors driving people to believe what they believe if change is going to happen. So here’s some Q&A that might help illuminate folks about what’s really happening.

What is faith?

Ultimately, faith is a coping mechanism. Humans are biologically-programmed to feel instinctual discomfort when faced with uncertainty. Since life is chronically uncertain, it can be more comfortable to commit your mind to the surety of faith; the idea that some greater force is out there governing things in our favor somehow.

Think about it: Do you feel better believing there’s an afterlife? Do you feel better believing you have someone to talk to? Do you feel better believing there’s a benevolent and powerful being out there who’s looking out for your best interests?

Of course you do!

In a clinical sense, faith is a balming behavior driven by our primal fear of pain and death. Since pain and death are fundamentally non-zero probabilities within every human lifespan, there’s no way to escape them. So if we can’t escape physically, we will escape mentally. We’ll create solutions (abstractions) that don’t exist in nature to dampen the emotional toll. Thus faith, in principle, is no different than an alcoholic drinking their problems away, only the side effects are cognitive instead of physical.

We know what happens to alcoholics, but what happens to folks who experience an abuse of faith? Here’s a few examples:

- The elder who forsakes their family because they don’t share the same religious views

- The child prevented from learning about science in school due to religious contradictions

- The woman who declines to protect herself because she has “faith in the lord’s protection”

- The wife who is forbidden by her community from divorcing her abusive husband

Applying a faith backed by nothing tangible to our real world is toxic. It triggers many biases that can cause us harm – tribalism bias, information bias, overconfidence bias, etc. It’s much easier to have faith in abstractions than tangible things that actually exist. It’s so easy, in fact, that folks get addicted to that faith and simply ignore, excuse, or defer aspects of their lives to it.

For example:

- “God will take care of me.” – Excuse not to act; laziness is easier

- “Thank you, God, for this food.” – Misplaced gratitude; easier to thank God than find those people actually responsible for making the food and thank them

- “God does not approve of that.” – Manipulative misdirection; easier to claim another authoritative figure does not approve than admit it is you yourself who takes issue with it

Again, I want to stress that religion hasn’t been all bad – lots of good has come of it! Organized religion has acted as a powerful conduit for the goodness within humanity in many tangible ways – charitable giving, rebuilding, and many forms of support have saved and improved many lives.

My intent is simply to show you a better way.

So, how can we redirect our faith in a healthier manner?

Faith in the abstract is the core troublemaker here, not the idea of faith itself. For instance, I have faith that the Sun will rise tomorrow. Am I wrong to make that assumption? Of course not! The Sun has been rising every day for billions of years. On the other hand, say I have faith that God will protect my child so she doesn’t need to be vaccinated. Am I wrong to make that assumption? Yes, absolutely – I’ve based my assumption on something intangible.

My challenge to you is to think about how you reinforce your faith; what you base it upon. For me personally, I have faith in my species; I’m what’s known as a “humanist.” I believe it’s okay to have faith in the things that tangibly work for us – our technology, our scientific methods, and the goodness (and badness) of the people around me. I’d argue this mentality enhances my ability to understand my environment and survive – pound for pound, I’ll survive better than someone who has faith in the intangible. I’ll also be happier because I have a superior understanding of why things are the way they are.

How can we cope with death without believing in an afterlife?

One of the primary marketing tactics of organized religion throughout history has been one’s supposed salvation (heaven) or damnation (hell) in one’s afterlife, based on one’s actions while alive. This fear-mongering tactic has given aristocracies an excellent vehicle for manipulating those less educated or more gullible than themselves. But lets ignore that and focus on how we might overcome this concept…

How can we cope without belief in an afterlife?

In short, by examining why you fear death: People think they fear death, but what they really fear is pain and their unfinished goals.

Death is an undulation in consciousness. How would you know you were alive unless you’d once been dead?

Alan Watts

Alan hits the nail on the head – death is what happens to you every night when you fall into a dreamless sleep. Did sleeping hurt? Did it harm you in any way? On that note, do you remember what it was like before you were born? Of course not! You do not fear these things; you do not fear death.

What you really fear, as I said, is pain and your unfinished goals.

Physical pain can be minimized or eliminated with medical science, mental pain can be minimized or eliminated with psychological therapies. These methods are human-driven and not reliant on the intangible; they work reliably. Don’t pray for pain to stop, consult a medical professional. Don’t talk with a priest, instead talk with a professional therapist. You will find far more happiness with your fellow qualified humans than with the obsolete institution of organized religion.

This concept also extends into the fear of unfinished goals – modern science has proven it can extend the human lifespan far more than the false hopes of religion ever could.

Why not simply rely on what works?

Religion may have it’s problems, but isn’t it a good moral guide at least?

I’ll defer to George Carlin on this one:

Ok, if religion is a poor compass for morality, then what’s a good one?

Something easy, simple, and timeless.

The Golden Rule: Seek to understand others and treat them as you would have them treat you.

What’s the difference between theists, agnostics, and atheists?

This trips a lot of people up: Agnosticism is about knowledge, while theism and atheism are about conviction (belief).

- All theists have conviction that God(s) exists

- All atheists fall into one of two types:

- Soft Atheism – No conviction that God(s) exists, but does not assert its impossibility

- Hard Atheism – No conviction that God(s) exists, but does assert its impossibility

- Agnosticism – The concept that the existence of God(s) is unknown or unknowable. Both atheists and theists can be agnostic. For example, a theist might claim they have “faith” in the existence of God, but know that its existence could never be proven; an agnostic theist

Does God exist?

Possibly, but certainly not in any conventional sense.

God is a relative idea: I am to an ant, what an ant is to a single-celled amoeba, and so on. We attribute “godhood” to feats of power – omniscience, omnipresence, omnipotence, superior (or inferior) morality, etc. Is it possible there are entities in the Universe that are so much more advanced in these areas that we can only comprehend them as Gods? Absolutely!

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Arthur C. Clarke

So, in a nutshell:

- Science is better than religion at understanding our world

- Humanism is better than religion at prioritizing the wellness of humanity

- The Golden Rule is better than religion at maximizing justice (morality)