Communication is important. Whether it’s happening in a school, on television, in a book, in-person, whatever, it molds our worldview.

You didn’t magically know what was “cool” as a child or how science works or what the Bible says. You were told these things by other people. We all were. In fact, our greatest strength as a species lies in our ability to retain and transmit information to one another. That interpersonal information network contains the sum of our knowledge and thus the sum of our power.

We’ve gone from grunts and primitive body language to oral and written languages to typing smiley faces on our social media-driven smartphones while riding the porcelain throne (don’t look at me like that, you’re a poop cruiser just like the rest of us and you know it!).

How we communicate matters and the collective label we place on the modern institutions and individuals who do most of the communicating is “the media.” In fact, the guy who wrote what you’re reading is also a very small part of said media.

The media began with good intentions and was generally a positive force in the Universe. Then, like so many other ideals exposed to reality, it went sideways…

Today, any educated individual can turn on any news channel and quickly realize the (mass) media has lost its way. I say “educated” because the modern media has become exquisitely engineered to capitalize on the ignorant.

None of this was intentional per se, there’s no evil conspiracy at work; it’s all simply the incidental byproduct of democratic capitalism and free speech. Where the presiding objective of the media was originally the spreading of truth, it has gradually (and naturally, given the context) eroded into the acquisition of profit.

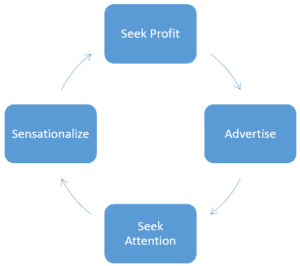

Consider the following cycle of motivation that drives the modern media:

- What motivates the modern media? Profit

- How do they make profit? Advertising

- How do they make more money advertising? By seeking attention

- How do they seek attention? Sensationalism

With this process in mind, let’s do a quick thought experiment…

Say you decide to build the most reliable and unbiased media source ever made. Say you miraculously accomplish this and manage to successfully establish a non-profit, donation-driven media entity that is solely focused on finding and disseminating evidence-based truth.

Because of this, people like you. So you get popular. But popularity has costs – you need more servers for your website, more paper for your newspaper, more boots-on-the-ground investigative journalists, etc. In the real world, donations won’t be enough. There will be a point where the expenses of your non-profit begin to eclipse your donation revenue.

Suddenly, the only option will be to turn to advertisers.

At first, you’ll be cautious about it. What’s one advertisement? But you keep growing. Now you need two. And so on. Gradually, as the above cycle rinses and repeats, the pressure to turn a profit simply to survive will exceed the value you place on your truth-seeking. One day, you’ll wake up, pick up your own newspaper, and realize your credibility no longer exists.

And that’s how the media shit the bed.

Of course, there are other factors too. Most notably how cultural barriers to entry and technological advances have changed the game.

In the early 20th century, the people in charge cared about their image. Credibility mattered. Not because they were better than us or somehow morally superior, as is sometimes naively assumed. Rather, because their incentive structure was vastly different. Their entire culture was vastly different: TV was new and novel, the masses were still sensitized to sex and violence, and reputations carried real weight and consequence. Making an error on national television could cost you your career.

So what the fuck happened?

Civil rights happened. Increased transparency happened; the upholding of free speech, technological revolutions amplifying the voices of the disenfranchised, the minorities, the shunned, the persecuted. A cultural golden age where anyone and everyone has a voice, devoid of censorship or consequence.

That happened!

No one in the 1950s could even conceive of this communication revolution, much less “l33t gamerz talkin politiks while shootin noobz on the YouTubez.”

Today, you might hear folks espousing the “good ole days” of the 1950s, reminiscing in nostalgia of that era’s supposed moral superiority. These people are ignorant and most likely white males. Ignore them.

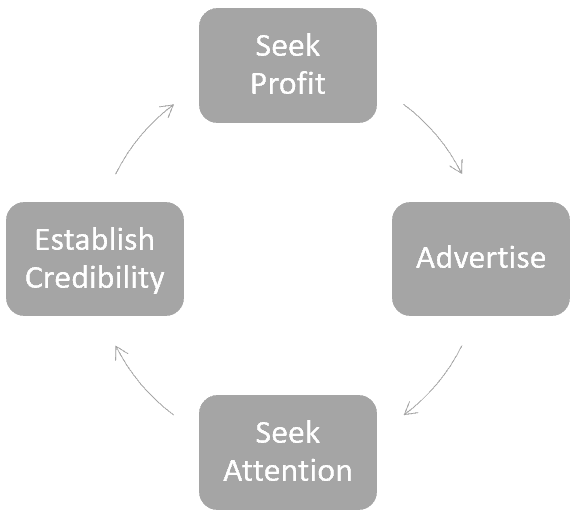

In reality, the early 20th century was absolutely rife with inequality and unfair barriers to entry. The only admirable quality of the era, in my view, is the value placed on intellectual integrity. But even that wasn’t special: Absent the extremely lucrative model of 24-hour engineered sensationalism in the present, the model of credibility naturally held precedence during those times. And where sensationalism caters to emotion, credibility caters to the intellect.

Early 20th Century

Now

Obviously, the world has changed. So let’s step away from the past and look at the challenges in front of us right now.

I think the following three are most relevant:

- How does one separate truth from untruth?

- Is total free speech ultimately healthy for a society?

- How could harmful rhetoric be regulated without regression into an Orwellian state?

These questions are hellishly complex issues, but I’ll take a crack at them anyway.

How do I separate truth from untruth?

“Truth” really is in the eye of the beholder. Only fools try to objectify truth; truth is a muddled, complex, subjective, and generally grey issue.

However…

There are tools that can help us remove the more glaringly obvious untruths. One is called “the Socratic Method.” I’m a huge fan of said method. Here’s how it works…

Say we’re trying to define a triangle.

Our initial definition might be “a triangle is a shape.” With the Socratic Method, we think about whether this definition truly describes the essence of a triangle by attempting to bring up exceptions: “Isn’t a circle a shape too?”

Voilà! Definition broken.

This time we’ll regroup and redefine a triangle as “a shape with three sides.” Pause and really think about this definition for a moment – can you find any other exceptions?

It just got a hell of a lot harder to find an exception, didn’t it?

But that doesn’t mean there isn’t one: “Isn’t a three-sided shape with one side curved not a triangle?” Dang, definition ruined again!

Ok, how about “a polygon with three straight edges and three vertices?” Can you find the exception?

Good luck finding one, because it’s the modern definition!

In a nutshell, the Socratic Method systematically eliminates weak arguments until a “least wrong” hypothesis is found. This is called “negative hypothesis elimination” and represents the essence of all philosophy and science – to arrive at the least wrong explanation of things; to travel towards truth and away from untruth.

There are lots of other ways to methodically sift out the bullshit (fairly, to all parties involved), but I like this one in particular.

Is total free speech healthy for a society?

At the risk of being a myopic, reductionist ass, I’ll binarily say no, it’s not healthy. Is it healthier? Yes. But it doesn’t deserve to be called “healthy.”

The damaging elements of free speech are very evident – misinformation, propaganda, ridicule, slander, libel, and fraud, to name a few issues, really do harm people. And it’s not a slap on the wrist, either. People die from these things. And realistically, most perpetrators don’t do these things specifically to hurt others. Most often it’s incidental to normal activity and/or financially motivated, or it could even be a very gradual result of something seemingly innocuous.

It’s about incentives, really. As long as the incentives are unchanged, the symptoms will persist.

How could harmful rhetoric be regulated without regression into an Orwellian state?

This is the big kahuna of the three questions – a variant of the age-old question “among us, who has the right to judge?” We know total free speech has harmful side-effects. But what to do about it? Should we do anything at all?

Well, it’s hard to deny that the rise of free speech has made the world a radically better place. So the risk of losing free speech is something that should never be taken lightly. This is why some people get so polarized about the issue, there’s a lot at stake! Yet, willful ignorance and complete dismissal of the subject out of fear is not the answer either.

As I said before, the problem lies with incentives. And believe it or not, most governments do a fairly good job minimizing the damage from said incentives (like the FTC and SEC in the US, for example).

But the two issues no one’s been able to touch with a 10 foot pole are misinformation and sensationalism. It’s simply political suicide to even approach regulation in these arenas: “So, Mr. Politician, you’re running on limiting the scope of the first amendment, is that it? Tell me, are you being suicidal intentionally or is someone coercing you?”

I call this the “first amendment moat” (FAM).

FAM is a tough, maybe impossible, nut to crack. We’ve gotten so spoiled about the first amendment that we can’t even conceive of fine-tuning it for our own benefit. We’ve become beligerantly puritanical about it, which is stupid because the white males who wrote the first amendment had no clue what the world would become. That’s not to dismiss them, mind you, they did great work for the times they lived in. But treating their design as gospel is just foolish and I don’t think they would have wanted us to do that.

But again, it’s a very difficult issue. The regulation of information is one of the first steps on the path to fascism. I think we’ve seen enough of that historically to at least have learned some lessons by now.

So it comes down to the following tradeoff…

Is the damage from misinformation and sensationalism great enough to warrant risking regulatory alteration to the first amendment?

I think it’s easier to perceive the risk of totalitarian regimes and fascism because not only is it omnipresent in Hollywood fantasies, it’s actually happened many times in history.

But what about the other side? What happens if we do nothing?

Misinformation and sensationalism are far more subtle, insidious even. They are silently molding generations. For example, will this desensitization to violence make us more warlike or less? Will it make us more inclined to protect the planet or less? Will it create more productive citizens or less? Who knows? How could we know? We’ve never seen it before!

Personally, I do worry that modern democratic nations excel at protecting themselves from just about everything… except themselves. It’s easy to forget the United States is an experimental government that’s only been around for about two and a half centuries. And if we’re being honest, great empires rarely fall, they crumble. And I really do wonder whether the apathy of my generation due to rampant misinformation and sensationalism is the vanguard of such a fall.

Again, it’s a complex and scary issue. I find myself leaning on us needing to be very careful about messing with free speech, but also needing to find a way to hold the media accountable for the truly harmful garbage they spew out to the public. Right now, I’m leaning on leaving it alone, because frankly I don’t think we’re mature enough as a civilization yet to regulate free speech, and that may be the case forever, who knows?

But let’s say we did decide to regulate it, for the sake of argument.

Assuming we get past FAM (which is an assumption of epic proportions), here’s an idea I’m chewing on – what if we simply remove government involvement as a sort of hybrid compromise? The vast majority of sensationalism is coming from a few media giants – major news networks, social media, and tabloids, namely. How can we remove their incentives to sensationalize and spread misinformation?

The way I see it, governments frequently use three incentive structures to get people to do what they want:

- Legislation enforced through authority structures

- Taxes

- Exclusivity

I think legislation is out – just about any law you could make regarding sensationalism and misinformation would be unenforceable from the get-go.

But taxes and exclusivity might work.

Say we create an independent media commission, likely initially set up by Congress (but definitely not by the executive or judicial branches for obvious reasons – the more power diversity the better). This entity would offer significant tax-breaks to media “members” who committed to removing misinformation and sensationalism from their business models and re-establishing the older credibility model. All media entities not within this federal organization would lack “membership status” and should/could be considered by the public as non-credible.

Regularly, the commission would monitor member media entities with a standardized series of audits to determine if they are upholding their right to be members. The audits would be required to be generic, publicly accessible at all times, the same for all members, and effective in revealing misinformation and sensationalist practices. Additionally, no one could hold power in this organization for more than a designated number of years during their lifetime (similar to how we limit presidents to a maximum of two four-year terms). Regular access-employees should also be cycled out. And, obviously, it needs to be very difficult for any other government entity to possess material influence over this commission once it’s set up.

The effect of such an organization is to divert revenue from sensationalist business models into shaping our culture for the better without actually modifying the first amendment or employing direct censure. The return on those diverted dollars is a healthier (regulated) news and media network. We tax tobacco, alcohol, and gambling, so why not tax sensationalists?

My idea probably has flaws, I wouldn’t doubt it. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t a worthy starting point for discussion, at least.