“Money is the root of all evil.”

I detest this catchphrase, it’s not even accurate! Here’s the actual quote:

“For the love of money is the root of all evil: which while some coveted after, they have erred from the faith, and pierced themselves through with many sorrows.”

Timothy 4:10 in the Bible (KJV)

Pursuing money to the exclusion of everything else is indeed foolish. But the idea that money itself is the culprit stems from ignorance, not wisdom.

Using money as a scapegoat for evil is a misguided way of perceiving the world, as money is merely a representation of value; a neutral tool. What people do with money is where evil resides. A rich man is not automatically evil, just like a poor person is not automatically evil. Evil has nothing to do with the state of a person and everything to do with their decisions and actions.

I’ve studied money for a long time and work in the financial sector professionally. If I’ve learned anything, it’s that most people don’t understand the truth of money; where it came from, why it’s important, and how money is currently shaping our civilization.

Admittedly, the subject of finance can be intimidating. So let’s start with the basics and then I’ll guide you to some rather profound conclusions.

First, the most basic and fundamental aspect of finance is the concept of value.

But what is value?

An economist might tell you value is “utility.” I’ll tell you value is what you decide it is.

Ultimately, value is an illusion; an arbitrary set of rules our species subjectively places upon the various configurations of matter around us. As social and group-oriented animals, we tend to believe something has value if our neighbor believes it has value: See that piece of garbage on the road? What if you discovered lots of people really wanted it? Is it still garbage? Of course not! One man’s trash is another man’s treasure (and maybe that original man’s treasure too when he finds out it’s worth something to others). Monkey see, monkey do! Trash is trash until it’s not.

Value is what we ultimately decide is valuable – all other definitions of value can be reduced to this fundamental principle.

So why does “money” have value? Well… what is money, really?

Money (currency) is ultimately a symbolic representation of trust: As I write this, I trust I can buy lunch for about 10 US Dollars. I’ve placed trust in pieces of paper to get me the food I need to stay alive. The restaurant is trusting that when they receive my $10, they can turn around and exchange it for whatever they need, of equal value, from a complete stranger that isn’t necessarily me.

Today, we take this exchange of money for granted, but thousands of years ago it didn’t exist. And it didn’t just spontaneously appear overnight; value was not always attributed to symbolic scraps of paper and metal. Instead, it resided in the actual things you needed to survive: Meat was valuable. Fur was valuable. A spear was valuable. These things were valuable due to their ability to do things: Meat could feed you. Fur could keep you warm. A spear could defend you or help you hunt.

But value is subjective.

If you have furs but not a spear, the spear is more valuable to you. If another person has spears but not furs, furs are more valuable to them. These imbalances happened everywhere and all the time. Unsurprisingly, humans (being the problem solvers we are), discovered it made sense to exchange what you have and don’t need for what you need and don’t have.

Thus, “trading” was born!

The first system of trade (or “commerce”) was “bartering,” which is the concept that I will give you one of my spears for some of your furs. Fundamental economic concepts like supply and demand originated here: Increases in supply tended to push materials outward, increases in demand tended to draw materials inward. These forces shifted resources like oceanic currents over time relative to the subjective requirements of various peoples, leading to a more even distribution of things like spears, furs, and meat to places where they were most needed and away from places where they weren’t.

This exchanging of resources gave us tremendous power over nature – If the natural environment constrained us from producing some good in one area, we could simply trade to get it from another: A man in the jungle could trade lumber for metals mined in a distant mountainous region. A nomadic woman could trade meat and furs for a local farmer’s greens. A farmer could trade a crop surplus for more land and/or animals. The possibilities were endless.

However, there is a fundamental problem with bartering – value transport.

In a bartering-based society, obtaining wealth means you have a lot of stuff. Stuff is hard to move. It’s awkward, heavy, and not always immediately useful. It also can’t be exchanged for some things; there will be situations where you need something someone else possesses, but simply do not have anything the other party values to barter with.

Obviously, this is a problem. How can we transport value more effectively?

Again, obviously (in hindsight), the solution was the development of currency. But I don’t think it happened like some folks imagine: In my view, a civilization makes the jump from bartering to currency very gradually. I have strong suspicions that what happened is the particular goods that possessed the greatest value to the most people were simply traded more frequently than other goods, causing them to slowly transform themselves into the first currencies.

What I mean by this is that humans, being more comfortable with familiarity as a rule, tend to stick with trading the things they understand. These familiar things could have been anything – furs, metals, animals, whatever. Let’s say they were metals. If it was commonly known that copper ingots could be used for manufacturing more resilient tools (add tin and you’ve got bronze!), then copper ingots would be in consistent demand everywhere since everyone needs more durable tools – hunting, farming, building, etc. This created a situation where the total amount of copper being traded at any given time (a concept known as “trading volume”) exceeded the amounts at which other goods were being traded.

Now if you’ve studied economics, you’ll know that goods with higher trading volumes tend to be more accurately priced (valued). The reason for this accuracy is a concept known as “arbitrage.” Arbitrage is simply taking advantage of price variations in or between various markets. For example, if copper costs $5 here, but $10 there, I’ll quickly buy all the copper I can for $5 and then sell it in the $10 market for a tidy profit. That’s arbitrage!

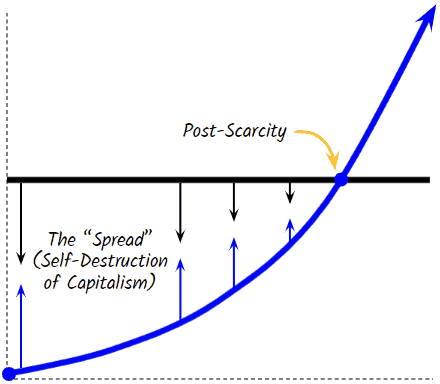

However, arbitrage comes with strings attached, notably the forces of supply and demand. If I bought a significant amount of copper for $5 here, and then tried to sell it there for $10, “here’s” price would increase (rising demand) and “there’s” price would decrease (increasing supply), eliminating the original opportunity for profit in the process (this arbitrage opportunity is known as “the spread” between both prices).

Arbitrage opportunities self-annihilate due to supply and demand (the spread of the opportunity compresses as trading actions are taken). This is precisely why goods that have high trading volumes tend to be accurately priced – there are significantly more people around to recognize arbitrage opportunities and compress the spread to virtually zero until the price hits something known as “equilibrium.”

So back thousands of years ago in our bartering-based society, more folks were gradually trading copper (let’s assume it was copper) at higher volumes and thus the price was more reliably stable. You want stability in a currency. A stable currency means I won’t be faced with selling my car for $17,000 and then turn around two days later and not be able to afford a candy bar with the same amount.

Before we knew it, we were comparing other goods in relation to our familiar and reliable standard of value – copper: “Those spears are worth about 4 copper ingots” or “I’ll take 6 deer off your hands for 3 copper ingots” and so on. Gradually, copper became the familiar staple of how people value all the things.

But as copper’s standardizing metric of value spread, inevitably things came to the fore that were not worth an entire copper ingot: “I just want an apple dude, I’m not giving you an entire copper ingot. How about I carve off a piece for you?”

Boom!

We’ve arrived at the dawn of currency-based commerce. From this point on, our civilization gradually began organizing “official” currencies, consisting of materials not necessarily intrinsically valuable (like copper) but instead simply backed by whoever was in charge. In the context of human history, people in charge tended to be kings, queens, aristocracies, religious leaders, etc. These leaders formed governments, which generally sanction their own particular variant of currency and do what they can to maintain it’s stable value and ensure it’s prevalent use (known as “monetary policy”).

Again, currency is about trust. We trust a currency to remain stable in the sense that others trust it too. If enough people stop trusting a particular currency, it collapses into something called “hyperinflation,” which is a fancy word for a currency losing it’s “purchasing power,” which is just what it sounds like.

Governments care about their currency, a lot. Most modern governments strictly regulate the purchasing power of their currencies via a central bank – a regulatory authority that takes various actions to influence the inflation or deflation of their currency in relation to its purchasing power (in the United States, this would be the Federal Reserve, or just “the Fed.”) Honestly, I could lecture blindfolded on modern US monetary policy for hours. But I respect your sanity, so I’ll do you a solid and skip over that.

Let’s get crazy.

Remember the “profound” conclusion I promised earlier. Are you ready for it?

The concept of money has an expiration date and it’s going to destroy itself.

Now what the hell do I mean by this? How can money destroy itself? How could money end, especially when it’s so deeply ingrained in every part of our society?

The answers lie in the deadly yet beautiful engine of modern capitalism.

Capitalism is merely the economic and political system in which a country’s trade and industry are controlled by private owners for profit, rather than by the state. Particularly, we want to examine the emergent properties of what makes up capitalism – namely, the modern “corporation” (read as: all profit-driven entities). Corporations are to capitalism what cells are to an organism, however they are individually far, far better designed for their purpose.

But what’s their purpose?

As you’re likely aware, corporations are designed to focus on only one thing – profit. They are exceedingly good at this. In fact, they are so good that they often harm things that get in their way. Why? Because they are objective-maximization entities.

An entity with the sole purpose of maximizing an objective will inevitably cause collateral damage, as it’s values are fundamentally incompatible with its environment.

Here’s an analogy…

Say you’re a robot who wants to maximize the amount of watermelons. If you were an intelligent objective-maximization entity, you might do whatever was required to obtain watermelons and/or watermelon seeds. You’d then start a farm and begin growing them. You’d practice a lot and get quite good at growing watermelons. Eventually, you buy more land with the profit you made selling watermelons, then plant more watermelons – rinse and repeat.

After awhile, you begin earning enough to hire geneticists to help biologically-engineer better and tastier watermelons. Every time nature throws a wrench in your plans – bugs, weeds, disease, etc., you overcome these obstacles by hiring smart people to develop technologies to conquer them. You are getting smarter yourself, all the time. Eventually, you get watermelons so resilient that no bugs, weeds, or diseases on the entire planet can cause them harm (and so tasty that no human can resist them). They become addictive.

But you don’t stop.

You begin buying up land with your profits. Eventually you’re so profitable that politicians and governments are in your pockets and you start influencing policy. Bit by bit, you begin taking over the land masses of the world with watermelon crops. One day, you realize that most of the work on your crops is being done by automation and robotics – humans are now the obstacles.

So, logically, you eliminate the obstacle…

You deceive those smart geneticists into building a super virus disguised as just another watermelon pesticide. Then you release it and watch humanity crumble to dust.

With humanity out of the way, you can freely begin terraforming the Earth to allow for more watermelons. That is, until you realize you can grow watermelons on other planets too and begin expanding out into the cosmos to maximize the number of watermelons for the rest of eternity.

…yeah, wow.

Obviously, an apocalyptic watermelon-maximization entity wouldn’t be realistic for a plethora of reasons. But can you say the same about a profit-driven entity? Believe it or not, you can’t. Because it’s already happening! Think about it: Today, how corporations pursue profit is often savage, cruel, and merciless. But that’s ok, because it’s “just business,” right? That’s the culture already forming around us – that this behavior is “normal.” But it’s not, is it?

In reality, corporations are extremely dangerous and toxic technologies that cause real collateral damage to our society in the form of environmental destruction and cultural dehumanization and suffering, which is precisely why they should be (and are) regulated by governments. As sociopathic, objective-maximization entities, corporations have no reliable internal moral compass; in fact, by their nature their moral compass is blind to all directions except towards their goal.

Now, it may surprise you to learn that I’m an ardent supporter of corporations; I think their utility far outstrips their drawbacks, given they are properly controlled.

Consider a chainsaw: In the hands of a responsible and trained adult, the chainsaw is a highly effective tool for cutting wood. But in the hands of a child, a chainsaw could cause devastating consequences. A corporation is no different in principle: In the hands of a healthy and balanced government, a corporation provides a boon to society in the form of jobs, innovation, and advancing technologies. But in the hands of a corrupt or weak government, inevitably causes great harm and destruction.

Fundamentally, corporations are tools like any other, technologies even. Probably the best way to think of them is by comparing them to computer programs, only they’re programmed to seek out and prioritize only one thing – the maximization of profit.

And there are myriad ways to produce profit up to and including selling rocks. A corporation that sells “pet rocks” is inherently no different than one that sells exotic sports cars (or watermelons). Both are objective-maximization entities seeking the same goal – profit.

And how profit is obtained has little meaning to a corporation, so long as it’s achievable.

Putting the immediate ethical concerns aside for the moment, perhaps the most important question we can ask is whether today’s systemic and widespread pursuit of profit will ultimately have a net positive or negative impact on us? Will the ends justify the means?

As someone who studies the nature of corporations and capitalism professionally, I believe the answer is yes – the end will justify the means.

To understand why, let’s examine why capitalism works…

Anyone who’s studied late 20th century history knows of the great “Cold War” between Russia and the United States, where fundamentally opposing ideologies butted heads for supremacy: Russia employed a system of communism (which is an extreme form of socialism) whereas the United States employed a system of capitalism. Socialism and capitalism are mutually exclusive philosophies and cannot coexist; they are antithetical to each other.

Socialism is the idea that we’re all equal and the fruits of labor should be shared. Capitalism is the idea that we’re not all equal and the fruits of labor should be owned by those doing the laboring. Not long ago, the world wasn’t sure which system would prevail. Only after the Cold War ended and Russia collapsed into economic ruin did we find out.

But why did capitalism prevail where communism did not?

Ultimately, capitalism prevailed because it’s fueled by one of the most important aspects of human nature: Where socialism is driven by idealistic benevolence at its core, capitalism is driven by something far more primal and realistic – greed.

Ever seen a truly benevolent animal? Me either. Think humans aren’t animals?

There are powerful biological reasons capitalism prevailed: Greed has always been fundamental to our survival; it’s an offshoot of self-preservation and self-interest, which are things that have aided our survival since the dawn of humanity.

5,000 years ago self-interest meant more food. Today, it means more money.

People are always and everywhere seeking assurances of survival. Sometimes that means seeking out powerful mates, other times it means seeking out money. Ultimately, it’s all the same thing – people don’t want to die. In a socialist or communist community, one relies on the support of others. In a capitalist community, one relies on oneself.

So which sounds better to you? Putting your survival in the hands of someone you’ve never met? Or taking control of your own life?

“Fuck that,“ you might say. ”I don’t want some stranger controlling my life.”

Understandable! Most people would agree with you. It’s easy to say you care about strangers, it’s much harder to mean it. Caring about strangers is alien to self-interest, which is biologically hardwired into us. We are simply not designed (or arguably evolved enough) to genuinely care about strangers. Not yet, anyway.

This is ultimately why the Russian experiment failed – their core premise of equality was morally sound, but realistically flawed. Humans are not advanced enough to be truly benevolent. We, by necessity of resource limitations, must focus on ourselves before others. And until we achieve a post-scarcity society, the symptoms of greed will necessarily be an inevitability.

But here’s the amazing irony: Capitalism itself will eventually create that post-scarcity society!

Capitalism has created a marvelous system of primal incentives to (incidentally) free us from resource-dependency. The byproduct of capitalism is the self-destruction of capitalism itself! Of money itself! Eventually, profit will have no meaning.

Ok, this requires some explanation – how can profit lose its meaning?

Well, what can your dollars buy today that they couldn’t before? What can a cell phone do today that a phone couldn’t do 10 years ago? How easy is it to sail across the Atlantic Ocean today compared to the 17th century? Is food more plentiful today than it was 50 years ago? How many diseases would have killed you a hundred years ago compared with today? How much easier is communication today than it was just 30 years ago?

Clearly, there’s a trend at play: The modern human’s access to resources is increasing exponentially. Our needs are being solved at an accelerating pace.

Simply extrapolate, friend.

Human beings have finite requirements. We need such and such water and such and such food, with entertainment and housing and travel needs. Our technology is getting better and better at meeting these requirements. While these basic living requirements remain largely static (our food and water intake are biologically fixed), the technologies that deliver them to us are rapidly advancing every year.

There will be a point where the purchasing power of a relatively tiny amount of money today will purchase everything a human could possibly need to live a healthy and happy life in the future.

$1 For Life

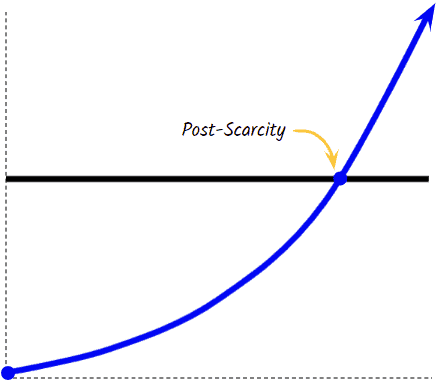

- Black = Resources required to sustain an average, happy, and healthy human lifespan; food, water, ideal home, traveling & recreational access, etc.

- Blue = The technological output of $1, inflation adjusted

Whether we gauge it to $1 or $100,000, this is the threshold of a post-scarcity society – where money’s usefulness gradually declines into virtually nothing proportional to the rising availability of resources due to technological advances; where people spread resources around often and for free and eventually stop charging for anything at all because it’s pointless. Why have human labor when you can just ask some robot or technology to do it faster and better?

Think about it: Corporations are objective-maximization entities. If corporations are taking over the world (which they clearly are/have), what are they doing?

They’re improving their products and services to deliver a profit. They’re playing arbitrage to capitalize on the spread between human need and available resources. It’s only a matter of time until this spread annihilates itself and the entire concept of what we value detaches itself from tangible resources altogether.

I know this sounds a bit crazy, but remember that supply and demand is a value phenomena – if the supply of resources is high enough, the price decreases to virtually nothing. If all resources have unlimited supply and our technology allows us unfettered access to them, then why is money necessary at all?

Pretty neat, huh?

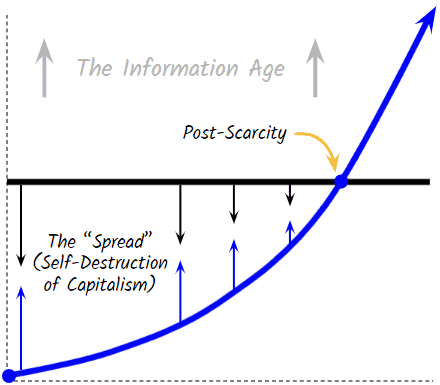

Now, does this mean that the entire concept of value is eliminated? Absolutely not. We will always value something. What we value is simply transformed. In a society with limited resources, the resources themselves are what’s valuable. But in a post-scarcity society, value is ascribed to something else entirely.

That something is information.

If everyone had every resource they could possibly want, what would another person be interested in that you have but they don’t? Information, of course! Whether this new information is contained within a story, art, music, or whatever, information is the new resource.

Information becomes the new currency, actually. But it’s not quite a currency, and it’s not quite bartering, either. It’s a new hybrid of both. In the era of information currencies, the capacity to produce new information will be the new founts of wealth, as once information is shared once, it can be replicated infinitely and immediately loses value from arbitrage annihilation (just like files being shared on the internet today). This places tremendous value on the person doing the creating; the source of the information.

Think of the implications of humans being resource-independent and highly valued for their ability to create. Because that’s what’s coming…